Translated from Latin, de Motu Amatorum would mean something like ‘on the movement of lovers.’ There’s a long list of scientific works that start with de Motu, including Aristotle on animals, Isaac Newton on anything in an orbit, and William Harvey on the heart.

This is not like these other works at all.

//

I wonder what is keeping my true love this night

I wonder what is keeping him out of my sight

I wonder if he knows of the pain I endure

And stays from me this night I’m not sure

Oh love are you coming your cause to advance

Or yet are you waiting for a far, far better chance

“I am coming for to tell you I’ve a new love in store

I am coming for to tell me I love you no more

For I can love lightly and I can love strong

I can love the old love till the new love comes on

I only said I loved you for to give your heart ease

And when I’m not with you I’ll love whom I please”

There’s gold in my pocket and pain in my heart

For I can’t love a man with too many sweethearts

You’re my first and only false love but it’s lately I knew

That the stronger I loved you the falser you grew

The spring grass grows the greenest and spring water runs clear

I’m sorry and tormented for the love of my dear

Your love it lies so lightly as the dew on the thorn

That’s there in the evening and away with the dawn

I Wonder What Is Keeping My True Love This Night, lyrics traditional, arr. Kate Rusby

This song is so pretty, this song is so sad. Why is this song so sad?

At night, a woman waits for her lover. He has not come, he was supposed to have come. Where is he? She asks the air. Suddenly he appears and speaks, only to repudiate her. He leaves again. She laments, alone.

Most versions of this song give the woman a full stanza of questions:

“Love, are you coming your cause to advance?

Or yet are you waiting on a far better chance?

Are you coming for to tell me you’ve a new love in store?

Are you coming for to tell me you love me no more?”

Two of these questions are hopeful. The latter two are not. She has time, over the course of a full stanza, to spread out, consider the possibilities. Perhaps it is over. The cadence resolves. She takes another breath.

When he arrives, his answer – the next stanza – is a perfect complement to hers:

“No, I’m not coming my cause to advance,

nor yet am I waiting on a far, far better chance.

I am coming for you tell you I’ve a new love in store,

I am coming for to tell you I love you no more.”

She breaths in, he breaths out, and even as he dismisses her there is a symmetry in his response that links the two of them. See how he carefully replies to every question she has asked, as if either he has been listening – or perhaps he simply knows her thoughts. They interact with measured formality tempered with intimacy.

What is so gutting about this version, then, is the elision of the female voice’s last two questions and male voice’s first two replies, such that the verse splits between them. She asks

“Oh, love, you coming your cause to advance?

Or yet are you waiting for a far, far better chance?”

and he interrupts

“I am coming for to tell you I’ve a new love in store,

I am coming for to tell you, I love you no more.”

That sound you hear is the sudden exhalation of the woman as the hope drains out of her. In the midst of her fantasy – that her lover was coming, or that he was tarrying for some beneficial reason – he appears and cuts her short. She was not ready. He was not listening.

//

I have been thinking about this woman, waiting. Maybe so much of the condition of the lover is about delay and expectation, how separation feeds longing but also distress. On the joyful side, is there anything more beautiful than your love approaching you? Sappho might say, no, no there is not:

Some men say an army of horse and some men say an army on foot

and some men say an army of ships is the most beautiful thing on the black earth. But I say it is

what you love.

Easy to make this understood by all.

For she who overcame everyone in

beauty (Helen)

left her fine husband

behind and went sailing to Troy.

Not for her children nor her dear parents had she a thought, no—

]led her astray

]for

]lightly

]reminded me now of Anaktoria who is

gone.

I would rather see her lovely step and

the motion of light on her face than

chariots of Lydians or ranks

of footsoldiers in arms.

]not possible to happen

]to pray for a share

]

]

]

]

]

toward[

]

]

]

out of the unexpected.

— Sappho fr. 35, tr. Anne Carson; If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho (Vintage, 2002)

For all the beauty of the opening priamel and its sudden, emphatic swerve (“but I say…”), my favourite stanza has always been the last, with the description of Anaktoria’s ‘lovely step’ and the ‘motion of light on her face.’ But beyond the beauty of these images there is, I think, a cleverer point to Sappho’s choice of words, for they describe not Anaktoria herself – her features, her loveliness – but rather they indicate that she is moving. She takes a step. Where is she headed? The light moves across her face. Towards Sappho, presumably.

What Sappho singles out is not Anaktoria with her, but rather the moments before she is by Sappho’s side; the moments as she moves closer, and closer still. Then, scholars think, the poem continues – but what happens? All that space, all those lacunae, and very little to go on. ‘Not possible to happen,’ Sappho sighs. Vagueness. Motion. Toward what? Or from what? The unexpected.

//

Zeno of Elea was a 5th century Greek philosopher, now primarily remembered as the author of a collection of paradoxes that argue for the impossibility of getting anywhere. In one of them, known as the dichotomy paradox, he argues that before a runner can cross a stadium she must first cross half of it, but before she can cross half of it she must cross half of that half-distance, or 1/4, and then before she can cross that one quarter she must cross half of that distance, or 1/8, and so on, indefinitely – there are infinite half-distances to be crossed, each one smaller than the last, and ultimately, Zeno concludes, this means that motion is impossible. We cannot cross infinite points in space in a finite amount of time. The runner stands fixed at the starting line.

Another of Zeno’s paradoxes argues that the faster of two runners (Achilles) will never overtake the slower of the two (the tortoise) so long as the tortoise has a head start in the race. For by the time Achilles has reached the point where the tortoise started from, the tortoise will have moved slightly further ahead, and then Achilles will reach the tortoise’s new position, but still the tortoise will have moved farther ahead again, and then for a third time, and a fourth . . . and every time the distance between the two runners will shrink, but still it will never be overcome.

Somewhere between these two paradoxes my brain, over the years, misremembered a spurious third option, a scenario where a runner got ever closer to the finish line but would be unable to cross it, for, after covering the halfway point she would have to cover the 3/4 point, and then the 7/8, then 15/16, then 31/32 . . . and like Achilles and the Tortoise, the runner would get closer and closer to the fixed finish post, but still would never reach it.

The historical record for Zeno’s original work is murky. Let us pretend that my misremembered innovation has some merit, at least until the end of this essay.

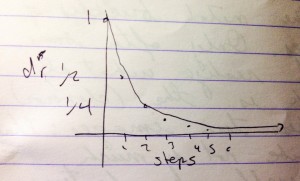

If we were to graph the runner’s approach to the finish line, we would get this shape:

That line will go on forever, bounded only by a limit – an asymptote – which is cannot cross over, or even touch. The zero line. The distance never not there.

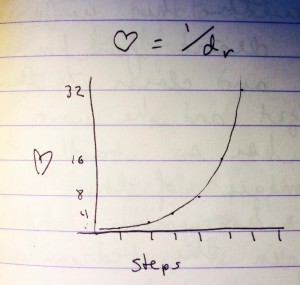

So let us return to Sappho, watching her beloved Anaktoria approach her. Nothing more beautiful. What if we said that with every step Anaktoria makes, Sappho’s desire grows as her beauty is more apparent? Perhaps desire is the inverse of distance. Think of your lover’s face moving in to kiss you for the first time, how your heart beats faster. We could graph that, too:

And that line, too, will go on forever, the line of desire, until we call Zeno on his bluff and say – “but we know we can move: we leave our house and go to work, we drive on the freeway to visit our family. The kiss happens. We reach our hand out in the morning and touch the arm of the person sleeping next to us. One more step, one more stade covered. The distance no longer there.”

And in our little graph, if desire is 1/distance[remaining], what is 1/0? I typed this into my calculator just now, and the answer came back: ‘error.’ ‘Undefined,’ a mathematician might say. Or perhaps, Sappho: ‘… out of the unexpected.’ Not possible to happen.

Let me give you a literary example of the undefined, the unexpected. In Joyce’s The Dead, the main character, a middle-aged man named Gideon, goes to a party with his wife. When they leave at the end of the evening he is full of swelling desire for her, for he has caught a secret glimpse of her earlier that evening as she stood on a stairwell transfixed by a melody heard in another room, and he was excited by her beauty, by her distance.

Gabriel had not gone to the door with the others. He was in a dark part of the hall gazing up the staircase. A woman was standing near the top of the first flight, in the shadow also. He could not see her face but he could see the terracotta and salmonpink panels of her skirt which the shadow made appear black and white. It was his wife. She was leaning on the banisters, listening to something. Gabriel was surprised at her stillness and strained his ear to listen also. But he could hear little save the noise of laughter and dispute on the front steps, a few chords struck on the piano and a few notes of a man’s voice singing.

He stood still in the gloom of the hall, trying to catch the air that the voice was singing and gazing up at his wife. There was grace and mystery in her attitude as if she were a symbol of something. He asked himself what is a woman standing on the stairs in the shadow, listening to distant music, a symbol of.

When they leave, they travel by carriage to the hotel they have rented for the night, and as they drop off the other members of their party Gideon recalls their courtship; the morning he received his first letter from her; the time of their honeymoon.

[W]ave of yet more tender joy escaped from his heart and went coursing in warm flood along his arteries. Like the tender fires of stars moments of their life together, that no one knew of or would ever know of, broke upon and illumined his memory. He longed to recall to her those moments, to make her forget the years of their dull existence together and remember only their moments of ecstasy. For the years, he felt, had not quenched his soul or hers. Their children, his writing, her household cares had not quenched all their souls’ tender fire. In one letter that he had written to her then he had said: Why is it that words like these seem to me so dull and cold? Is it because there is no word tender enough to be your name?

Like distant music these words that he had written years before were borne towards him from the past. He longed to be alone with her. When the others had gone away, when he and she were in their room in the hotel, then they would be alone together. He would call her softly:

—Gretta!

Perhaps she would not hear at once: she would be undressing. Then something in his voice would strike her. She would turn and look at him. . . .

He wants her so badly and yet, still, when they reach the hotel he stand unmoving in their rooms, unsure of what gesture to make, how to cross this final bit of distance between them. Suddenly she moves towards him to kiss him and he thinks, oh, she has done it– yet what follows is not the passion he had imagined but a tearful recollection on her part, the revelation of a boy who loved her once long ago, in her girlhood before she met him, a boy who sang the song she had been transfixed by earlier that evening. They break apart; she collapses on the bed. A boy who had loved her and died. Gideon never even knew. There is so much distance between them now. Error, we might say. Undefined. Out of the unexpected.

But Sappho watches Anaktoria approach her and her desire only grows, expectant. The light moves across Anaktoria’s face brightly. Nothing more beautiful.

//

| Leyg ikh mir in bet arayn Un lesh mir oys dos fayer Kumen vet er haynt tsu mir Der vos iz mir tayer |

I lie down in bed alone and snuff out my candle Today he will come to me who is my treasure |

| Banen loyfn tsvey a tog Eyne kumt in ovnt Kh’her dos klingen – glin glin glon Yo, er iz shoynt noent |

The trains run twice a day One comes at night I hear them clanging – glin glin glon Yes, now he is near |

| Shtundn hot di nakht gor fil Eyns der tsveyter triber Eyne is a fraye nor Ven es kumt mayn liber |

The night is full of hours Each one sadder than the next Only one is happy When my beloved comes |

| Ikh her men geyt, men klapt in tir, Men ruft mikh on baym nomen Ikh loyf arop a borvese Yo! er iz gekumen! |

I hear someone coming, someone raps on the door Someone calls me by my name I run out barefoot Yes! He is come! |

(Leyg Ikh Mir, Joseph Rolnick, translation by Kristina Boerger)

‘Darkly expectant’ is how composer David Lang describes this poem. Another woman waiting. There is so much to like about Lang’s setting, the ascending lines of every syllable like questions – is he here, is he here? – and the straight, dark drone that creeps in underneath like doubt. Counterpoint to expectation. The third verse is the darkest, no longer describing the process of waiting at all but rather the effect of their beloved’s absence – and here the hopeful, questioning line ceases altogether and there are only straight, dark, unsettled chords . . .

Then, in the final verse, she hears him, she wakes up, and a solo voice comes in with a new motif over the choir, expectant once more. This new voice repeats the first two verses, omits the dark third, and the moves to the fourth, where she runs barefoot out of the house – he is come, he is come! The final word, repeated over and over. Gekumen gekumen. He is come.

The song finishes before they meet, before that last moment of distance has been crossed. I imagine her step on the ground, the motion of moonlight on her face. Her desire swells. She has not seen him yet. She has been waiting. When she sees him, when there is no more distance between them, what happens?

The train will always run. Live next to a train track for any amount of time – as I do, right now – and you will start to absorb its schedule, its passage by your life. The rumble seeps into you. And so the train comes twice a day and her beloved comes once, a light against the dark hours. But still every night, that shiver – the question of where he is, the excitement and the expectation and the question – where is he, where is he? He is near. He gets closer. The hours of the night are so unhappy, but soon he will be here. Her desire swells – yet always, always, the subtle underlying fear of the unexpected. ‘I am coming for to tell you, I love you no more.’

The trains will still roll by, of course. All the watches of the night will continue, keep their rhythms, only she will lie in bed, breathe in and out on her own. No questions any more. Nothing to wait for. The train will come by and maybe it shakes the room, a different kind of shiver. Her breath grows ragged. Many hours still.

//

//

Glin. Glin. Glon.