Socrates

Then an eye viewing another eye, and looking at the most perfect part of it, the thing wherewith it sees, will thus see itself.

Alcibiades

Apparently.

Socrates

But if it looks at any other thing in man or at anything in nature but what resembles this, it will not see itself.

Alcibiades

That is true.

Socrates

Then if an eye is to see itself, it must look at an eye, and at that region of the eye in which the virtue of an eye is found to occur; and this, I presume, is sight.

Alcibiades

That is so.

Socrates

And if the soul too, my dear Alcibiades, is to know herself, she must surely look at a soul…

– Plato, First Alcibiades

“Keep me as the apple of the eye,” sings the psalmist in Psalm 17. “Hide me under the shadow of thy wings.” Only that’s not what he sang, not quite. The Hebrew word that the translators of the King James Bible rendered here as ‘apple’ is ‘iyshown, which means not ‘apple’, but ‘pupil.’ Keep me as the pupil of the eye || Hide me under the shadow of thy wings. One of the basic principles of poetic structure in the psalms is parallelism between each side of a verse. These entreaties, then, ask the same thing twice: enfold me, cover me, keep me safe from harm, from dust, from wind and blinding light. Blink down your eyelid. Fold over your wings. Bring me inside of you.

Some time ago I thought of this phrase, idly, and then I wondered, why an apple? For the sweetness? I was thinking of the way we use the idiom in modern English, to describe a thing or person cherished. I had always assumed that the apple referred to an external object, something so lovely to look upon that it engendered affection, that seeing it becomes almost necessary. And yet— no. To call someone the apple of your eye is not to set them up as an object distinct from you; it is rather to take them into yourself entirely – to identify them as a part of your own body.

When we look straight at someone, we also see ourselves, reflected back in their pupils. The ancient Israelites noticed this, and the word they used for pupil in this psalm, ‘iyshown, more literally translates to ‘little man.’ Keep me as the little man of the eye. The Latin word for pupil, pupilla, is nearly the same: a diminutive form of pupa, ‘young girl.’ We might remark that both these terms focus not on the pupil itself; rather, they focus on the appearance of something else – a second person, reflected in the first person’s eyes.

Both pupa and its companion form pupus, ‘young boy’, derive from a stem ‘pe-‘ in Latin which means ‘to beget.’ I wrote above that I had thought of the ‘apple of the eye’ as something that engendered affection, but this is the opposite: a thing engendered. Look straight at another person, and you come into being outside of yourself, a tiny little you shining on their eye. At the same time they come into being inside you. The apple of your eye. I am in front of you, I am already inside you. Blink down your eyelid, fold over your wings, cover me. Keep me safe as the apple of your eye.

But why an apple? I left that question unanswered. And when I wrote that the Hebrew ‘iyshown means ‘pupil’ rather than ‘apple,’ I more accurately should have said: Apple can mean pupil, too. You can read it in Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, when Oberon pours his love potion onto Demetrius’s eyes:

Flower of this purple dye,

Hit with Cupid’s archery,

Sink in apple of his eye.

Shakespeare didn’t invent the phrase. You can find it in dictionaries as well, Randal Cotgrave’s Dictionary of the French and English Tongues (1611) and John Florio’s A World of Words (1598,) though it might be mentioned that Florio and Shakespeare knew one another. But should you keep pushing on this trail, eventually you will end at the feet of King Alfred, ruler of Wessex from 871 to 899. We started with King James and his bible. Here is another king, another biblical translation. Alfred either translated, or supervised the translating of, fifty psalms from the Latin Vulgate into English. When he reached Psalm 17 (Psalm 16, in the Psalter he was reading) he read pupillam intus in oculo and wrote æplum on his eagum. Apple of the eye.

In the Old English Alfred wrote and spoke, æplum could mean apple. It could also mean, simply, a round thing, a ball. Æplum on his eagum. Ball of the eye. The hard centre. The pupil was commonly thought of as a solid, a small sphere of black inside the larger sphere of the eye. Keep me as the ball of the eye. The dark, mysterious core of the eye that, somehow, permits sight. The hard centre of oneself – yet a precious, fragile thing. A thing that needs the protection of the blinked eyelid, the folded wing.

All these terms to describe the pupil might be called metaphors, in that they describe the object in question through reference to something else. The language of the psalmist is also metaphorical, if we extend metaphor to encompass simile. Keep me as the apple of the eye. Now, Aristotle tells us that metaphors are useful because they bring about learning and produce new facts. “It is from metaphor that we can best get hold of something fresh,” he asserts in the Rhetoric. When we use one word to describe another thing, the mind must work to catch up and find the point of similarity between what it expected to hear and what it actually heard. “Metaphors must be drawn,” he explains further, “from things that are related, but not obviously so related.” The listener is impressed by this unexpected turn because the connection was not evident until laid before her. She must be inspired, he continues, to exclaim “Yes, to be sure; I never thought of that.”

Aristotle focuses on the point of sameness between two ideas; the way this commonality illuminates the features of both and the knowledge that arises from this illumination. The images slide over one another and suddenly some part of them lines up so perfectly that they seem to be one and the same. In a sea of intersecting and overlapping images our eye is drawn to this point of clarity. We notice something we hadn’t before. But one can also notice the friction of two distinct concepts fitting against one another poorly. This friction generates the heat of its own fact, lighting up the precise points where the two thoughts differ. Perhaps these are edges you had not noted before. Oh, to be sure; I never thought of that.

What about the friction between two metaphors, between pupil as little person and pupil as apple? Keep me as…. I place these two ideas onto one another and I hit a snag; something grinds. To be kept as the ball of the eye is to be made into something else; taken inside another. It’s easy, it’s simply, it’s lasting. To be the little person of the eye is different. Look at someone and she will appear in your pupil, but blink down your eyelid, as the psalmist seems to ask, and what happens? You’re not looking at her any longer; the image vanishes. So perhaps this is not an act of bringing her inside yourself but rather letting her always be just adjacent, just outside. Moreover, the act is mutual; it requires both her presence and your gaze. Blink and she is gone. Keep me as the apple of the eye. Never stop looking at me.

Let us take one further step back and ask, how do these differences rub up against the real world? For in fact the pupil is not a solid sphere; it is not a little person; it is not a substance at all. The pupil is a hole, a lack, a trap into which light falls. The pupil is black because it yields nothing, gives up no light. We look at someone – someone stands before us – and the light coming off her falls into us, strikes our ocular nerve, and is transfigured as an image in our brain.

Except, of course, for the cornea that covers the pupil and iris. The primary role of the cornea is to refract light, focussing it like a camera lens before it falls into the aperture, the pupil. Yet sometimes it reflects a little light, and the person standing before us sees herself too: a little human born on the eye, teetering on the edge of our pupil, not quite falling in.

So the apple of your eye, then, the pupilla, the ‘iyshown, is both yourself and the external world. It is the little piece of the person staring into your eyes that refuses to fall in, just as, if she turns her gaze to you, there is a piece of you reflected back in her eyes – yet all the while you are both also falling into the other, rattling through their optic nerve, lighting up neurons. All of this playing out on this mysterious core-that-is-nothing, the apple of the eye. Were I in the business of metaphor I might say that this is love: the balance of sublimation into another against the assertion of one’s own independence. Played out in this tiny, delicate core. The æplum. The ‘iyshown.

Were I in the business of metaphor I could say this balance is love, but I might not: instead I might say that the balancing act is itself an act of metaphor: the overlapping of two individuals. What truths light up? What facts grind out in the friction between them?

I quoted a passage from the First Alcibiades at the opening of this piece – a pseudo-Platonic dialogue that, ironically, was once used as an introductory text for students of philosophy because it encapsulated so many of Plato’s ideas. Now it is thought to be, perhaps, not the genuine article but an imitation; a metaphor betrayed by its troubling points of friction. No matter. The Socrates in this passage makes it sound so easy – the steady gaze; the ready truth. He doesn’t expect to see anything other than that which is already there. One’s own eye. One’s own soul. A discrete thing, already formed. Yet looking into another’s eyes can engender sparks of the new, and some novel emotion or fact arises. From the similarities and differences new knowledge is made. Socrates makes it sound so easy. When I think about it, I feel dizzy. Is it so easy?

Two truths approach each other. One comes from inside, the other from outside,

and where they meet we have a chance to catch sight of ourselves.

The man who sees what’s about to take place cries out wildly: “Stop!”

Anything, if only I don’t have to know myself.”

And a boat exists that wants to tie up on shore–it’s trying right here–

in fact it will try thousands of times yet.

Out of the darkness of the woods a long boathook appears, pokes in through the open window,

in among the guests who are getting warm dancing.

– Tomas Tranströmer, Preludes (II) trans. R Bly

No, cries the man in Tranströmer’s poem. Anything but this. It’s not so easy, maybe. Not all the time. You might be alarmed, you might not want to see what is coming — yourself; something new. You might cry out for comfort. Keep me as the apple of the eye. Cover me.

Whatever that means.

![]()

![]()

Notes

Old English nouns change their endings depending on their grammatical role in a sentence. I have used the form ‘æplum’ for consistency with the quoted passage from Alfred’s Psalter, and there are a wide variety of spellings used with Old English texts, but the Dictionary of Old English lists all under the headword ‘æppel.’ I should also note that Alfred uses the phrase in other texts as well; the first instance is in his translation of Gregory’s Cura Pastoralis.

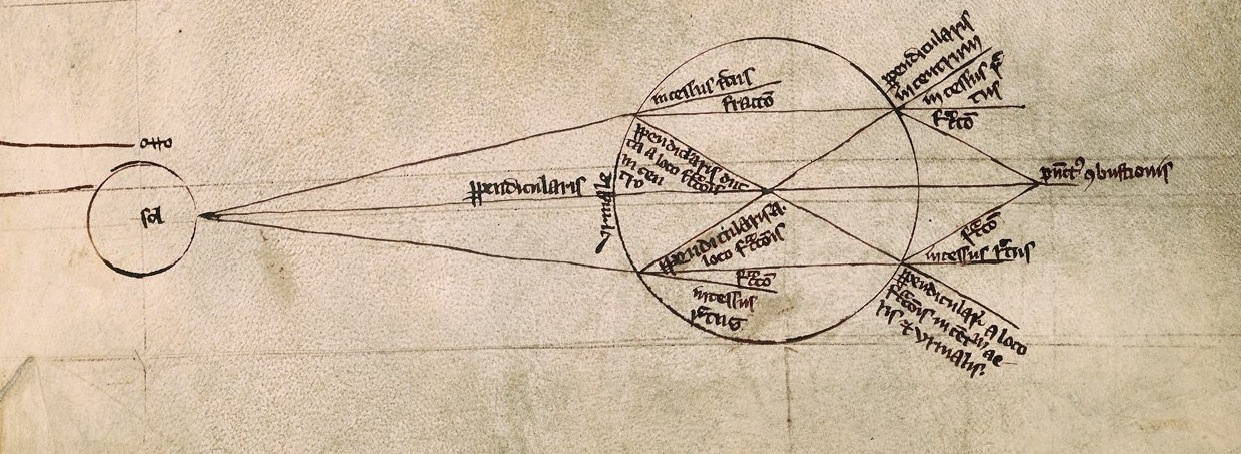

Elsewhere, I have used W.R.M. Lamb’s translation of Plato, and W. Rhys Robert’s translation of Aristotle. Robert Bly’s translation of Tomas Tranströmer can be found in The Half Finished Heaven, Bly’s selection and translation of Tranströmer’s poetry, published by Greywolf Press. I found Florio and Cotgrave’s dictionaries through the Lexicon of Early Modern English, but scans of both seem to be widely available elsewhere online. Section dividers are modified from Thomas Young’s sketch of two-slit diffraction, and the header image is taken a scan from Roger Bacon’s de multiplicatone specierum, showing the path of light being refracted through a spherical glass of water. Both images are in the public domain.

1 comment for “Apple of My Eye”